I’m going to be a little bold in this post and suggest if you are developing for SQL Server, the screenshot to the left and above shows something that is, well, wrong. I can hear you thinking,

I’m going to be a little bold in this post and suggest if you are developing for SQL Server, the screenshot to the left and above shows something that is, well, wrong. I can hear you thinking,

“What’s Wrong With That Output, Andy?”

I’m glad you asked. I will answer with a question: What just happened? What code or command or process or… whatever… just “completed successfully”? Silly question, isn’t it? There’s no way to tell what just happened simply by looking at that output.

And that’s the point of this post:

You don’t know what just happened.

Sit Back and Let Grandpa Andy Tell You a Story

I was managing a large team of ETL developers and serving as the ETL Architect for a large enterprise developing enterprise data engineering solutions for two similar clients. Things were winding down and we were in an interesting state with one client – somewhere between User Acceptance Testing (UAT) and Production. I guess you could call that state PrUAT, but I digress…

The optics got… tricksy… with the client in PrUAT. Vendors were not receiving pay due to the state of our solution. The vendors (rightfully) complained. One of them called the news media and they showed up to report on the situation. Politicians became involved. To call the situation “messy” was accurate but did not convey the internal pressure on our teams to find and fix the issue – in addition to fixing all the other issues.

There were fires everywhere. In this case, one of the fires had caught fire.

Things. Were. Ugly.

My boss called and said, “Andy, can you fix this issue?” I replied, “Yes.” Why? Because it was my job to fix issues. Fixing issues and solving problems is still my job (it’s probably your job too…). I found and corrected the root cause in Dev. As ETL Architect, I exercised my authority to make a judgment call, promoted the code to Test, tested it, documented the test results, created a ticket, and packaged things up for deployment to PrUAT by the PrUAT DBAs.

Because this particular fire was on fire, I also followed up by calling Geoff, the PrUAT DBA I suspected would be assigned this ticket. Geoff was busy (this is important, don’t forget this part…) working on another fire-on-fire, and told me he couldn’t get to this right now.

But this had to be done.

Right now.

I thanked Geoff and hung up the phone. I then made another judgment call and exercised yet more of my ETL Architect authority. I assigned the PrUAT ticket to myself, logged into PrUAT, executed the patch, copied the output of the execution to the Notes field of the ticket (as we’d trained all DBAs and Release Management people to do), and then manually verified the patch was, in fact, deployed to PrUAT.

I closed the ticket and called my boss. “Done. And verified,” I said. My boss replied, “Good,” and hung up. He passed the good news up the chain.

A funny thing happened the next morning. And by “funny,” I mean no-fun-at-all. My boss called and asked, “Andy? I thought you said the patch was was deployed to PrUAT.” I was a little stunned, grappling with the implications of the accusation. He continued, “The process failed again last night and vendor checks were – again – not cut.” I finally stammered, “Let me check on it and get back to you.”

I could ramble here. But let me cut to the chase. Remember Geoff was busy? He was working a corrupt PrUAT database issue. How do you think he solved it? Did you guess restore from backup? You are correct, if so. When did Geoff restore from backup? Sometime after I applied the patch. What happened to my patch code? It was overwritten by the restore.

I re-opened the ticket and assigned it to Geoff. Being less-busy now, Geoff executed the code, copied the output into the Notes field of the ticket (as we’d trained all DBAs and Release Management people to do), and then closed the ticket. The next night, the process executed successfully and the vendor checks were cut.

“How’d You Save Your Job, Andy?”

That is an excellent question because I should have been fired. I’m almost certain the possibility crossed the mind of my boss and his bosses. I know I would have fired me. The answer?

Output.

Documented output, to be more precise.

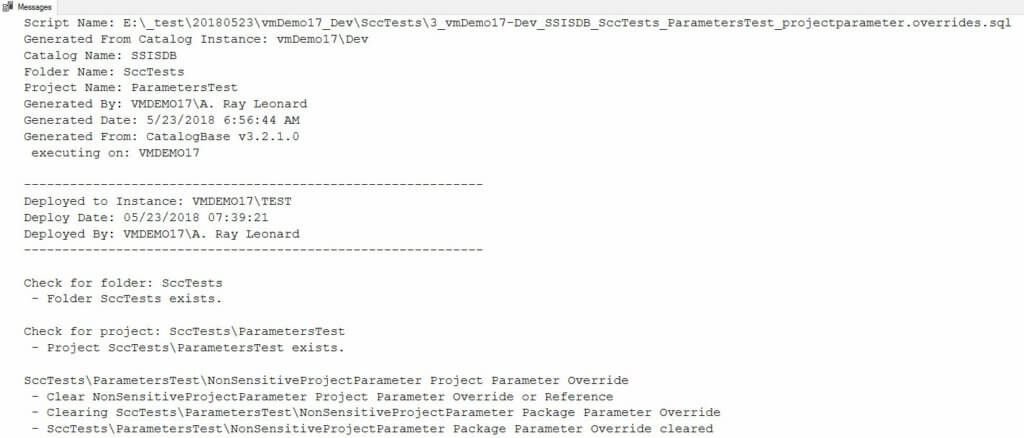

You see, the output we’d trained all DBAs and Release Management people to copy and paste into the Notes field of the ticket before closing the ticket included enough information to verify that both Geoff and I had deployed code with similar output. It also contained date and time metadata about the deployment, which is why I was not canned.

Output Matters

Compare the screenshot at the top of this post to the one below (click to enlarge).

This T-SQL produces lots of output. That’s great. Sort of.

“There’s no free lunch” is a saying that conveys everything good thing (like lunch) costs something (“no free”). And that’s true – especially in software development. Software design is largely an exercise in balancing between mutually exclusive and competing requirements and demands.

If it was easy anyone could do it.

It’s not easy. It takes experienced developers years to develop (double entendre intended) the skills required to design software – and even more years of varied experience to build the skills required to be a good software architect.

The good news: the output is awesome.

The bad news: the output is a lot of typing.

“So Why, Andy? Why Do All The Typing?”

That’s not DevOps. That’s wishful thinking.

You’ve probably heard of technical debt. This is the opposite of technical debt; this is a technical investment.

Technical investments are time and energy spent early (or earlier) in the software development lifecycle that produce technical dividends later in the software development lifecycle. (Time and energy invested earlier in the project lifecycle always costs less than investing later in the project lifecycle. I need to write more about this…) What are some examples of technical dividends? Well, not-firing-the-ETL-Architect-for-doing-his-job leaps to mind.

This isn’t the only technical dividend, though. Knowing that the code was deployed is important to the DevOps process. Instrumented code is verifiable code – whether the instrumentation supports deployment or execution. Consider the option: believing the code has been executed.

That’s not DevOps. That’s wishful thinking.

Measuring Technical Dividends

Measuring technical dividends directly is difficult but possible. It’s akin to asking the question, “How much downtime did we avoid by having good processes in place?” The answer to that question is hard to capture. You can get some sense of it by tracking the mean time to identify a fault, though – as measured by the difference between the time someone begins working the issue and the time when they identify the root cause.

Good instrumentation reduces mean time to identify a fault.

Knowing is better than guessing or believing.

The extra typing required to produce good output is worth it.

Good Output

In this age of automation, good output may not require extra typing. Good output may simply require another investment – one of money traded for time. There are several good tools available from vendors that surface awesome reports regarding the state of enterprise software, databases, and data. DevOps tools are maturing and supporting enterprises willing to invest the time and energy required to implement them.

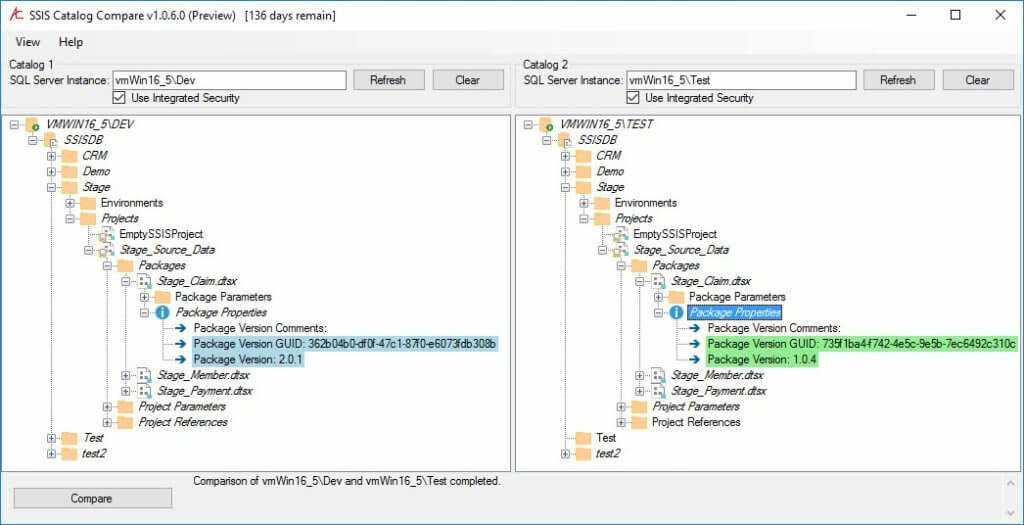

One such tool is SSIS Catalog Compare which generated the second screenshot. (Full disclosure: I built SSIS Catalog Compare.)

SSIS Catalog Compare generates scripts and ISPAC files from one SSIS Catalog that are ready to be deployed to another SSIS Catalog. Treeview controls display Catalog artifacts, surfacing everything related to an SSIS Catalog project without the need to right-click and open additional windows. (You can get this functionality free by downloading SSIS Catalog Browser. Did I mention it’s free?)

In addition, SSIS Catalog Compare compares the contents of two SSIS Catalogs – like QA and PrUAT, for example. Can one compare catalogs using other methods? Yes. None are as easy, fast, or complete as SSIS Catalog Compare.

Discount!

For a limited time you can get SSIS Catalog Compare for 60% off. Click here, buy SSIS Catalog Compare – the Bundle, the GUI, or CatCompare (the command-line interface) – and enter “andysblog” without the double-quotes as the coupon code at checkout.

Conclusion

Whether you use a tool to generate scripts or not, it’s a good idea to make the technical investment of instrumenting your code – T-SQL or other. Good instrumentation saves time and money and allows enterprises to scale by freeing-up people to do more important work.

:{>

Comments