Introduction

This post is the ninth part of a ramble-rant about the software business. The current posts in this series are:

This post is an introduction to metaproblems and discusses a common metaproblem: drama.

Problems

I define a problem as an unsolved issue. It could be minor. Or it could threaten your project, llivelihood, or even your life. Problems share some characteristics:

- Problems are not symptoms.

- Problems are not effects.

- Problems rarely scale.

The symptoms of a problem are related to the problem. We usually think of symptoms medically. If you have a common cold you exhibit symptoms. The symptoms indicate you have a cold, but they are not the root cause of the cold. The root cause is something else – some virus or other. As I type, Emma Grace is sneezing. Sneezing is a symptom, she’s either coming down with a cold or reacting to an allergy. It’s also snowing, so the weather is a problem.

We can treat the symptoms. In fact, Christy just gave Emma an antihistamine to alleviate her sneezing. Treating the symptoms is not without merit – sometimes it’s the best you can do.

As a result of Emma’s cold, she cannot go play in the snow that is falling as I type. The snow also caused the postponment of SQL Saturday #30 in Richmond. Both are examples of effects of a problem.

Emma’s cold is running its course. The snow will continue falling. The actual problems are: the cold and the weather. Emma could catch another cold – that would be a different problem. The symptoms could grow worse; that would fall under more symptoms. Emma’s cold remains the problem. The snow is forecast to fall into the evening. Other activities are cancelled or postponed in our area this weekend as a result. These are more effects. The problem is still the weather. The problems don’t scale, though the symptoms and effects can and often do.

Metaproblems

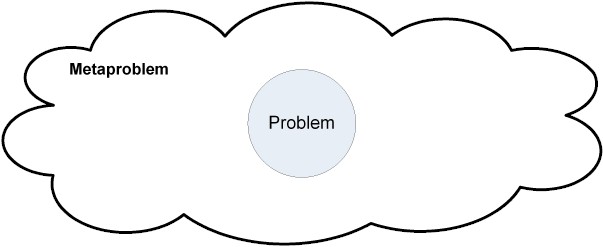

The diagram above is my attempt at visualizing a metaproblem (yes, I made up another word. I can do that. I’m an author.). A metaproblem is a problem with a problem.

An example of a metaproblem is: Emma is upset that she can’t play in the snow with the boys. Another example: I’m bummed about postponing SQL Saturday #30 because some speakers and attendees won’t be able to make the new date.

Metaproblems are manufactured by people. In business, the most prevalent category of metaproblems is drama.

A server crashes due to a hard drive failure. Your boss calls you screaming that it’s your job to anticipate hardware failures and replace hard drives the week before they fail. The failed hard drive is the Problem. Your boss’s illogical emotional rant is drama.

Drama is More Work

For everyone involved in the actual solution, drama is just more work. The time spent responding to the overreactions of others is really time that could be spent solving the Problem.

Some Irony

When the Problem is solved, the people manufacturing the drama will secretly congratulate themselves for their “contribution” – believing the additional workload and stress they added to the hearts and minds of those actually solving the Problem (punching them in the brain) helped in some way.

Nothing could be farther from the truth.

If you don’t have your hands on or in the solution, you can do one of three things to help:

- Get your hands on or in the solution.

- Stay out of the way of those with their hands on or in the solution.

- * (Not yet… I’m saving this for a follow-up post in this series)

Overcoming Drama

How do we deal with drama when faced with it? That very question is flawed. You cannot deal with drama when faced with it: It’s not within your realm of influence, it’s nothing you can change. The root of drama is in someone else’s mind and you cannot affect that unless you’re Matt Parkman.

Drama, when it is occurring, is best identified as such and then ignored. In the example above, explaining the hard drive failure is the Problem and the steps you’re taking to replace and rebuild it should suffice. If it doesn’t, you could be the victim of a Crappy Job. Personally, I don’t even acknowledge the drama that attaches itself to Problems.

Serious efforts at curbing drama happen before and after drama strikes.

Before it happens, recognize and communicate the potential impedance drama adds to any real Problem. After the fact, point out the Problem and the metaproblems, starting with the drama. Be specific about the amount of time it took to solve the Problem and the additional time wasted mitigating the drama.

Conclusion

I view Problems as challenges. When I’m feeling clever, I refer to obstacles as “something to overcome.” They represent an opportunity for me to learn something and demonstrate that knowledge on the quest.

* I’ll dive into a better response to Problems in an upcoming post in this series.

:{> Andy

One of my former managers used to say that you had to be able to tell the difference between what was actually happening and your STORY about what was happening. When the poop hits the fan, nobody wants to hear your story. They want to hear what’s happening.

You can see it on TV news shows. Some of them tell the news, and some of them tell stories (Anderson Cooper, Jim Cantore, etc.) In business, the story just gets in the way.

It was so amusing to hear him butt into a crisis. "Okay! I get it. That’s your story. Take thirty seconds to write down the bullet points of your story on this whiteboard. When you’re done, we’re going to stop talking about your story, and we’re going to focus on the problem. You can tell me your story afterwards. Ready, go."

This series keep getting better and better, thanks for writing them. I forward them regularly to my boss, now will she listen? oh wait, she just read this comment! >>Hi Boss<<

Thanks for reminding me of the CJT. Man is that great!

🙂